“You know, this is quite interesting literature. It’s a peculiar kind of communism, it’s hooligan communism.” — Lenin, on 150 000 000 by Vladimir Mayakovsky

I.

This is not a poem for spectres

and other non-corporeal things,

persisting after defeat.

In these streets stalk

hobgoblins, frightful

gargoyles

with skins of concrete.

Here are the rabble of knaves

and hooligans,

the ugly part of the crowd, outside

the mythologised masses.

Here,

we say: Europe is haunted

by more than workers.

This manifesto,

is not for trade unionists,

trading stock in authenticity

through investment in accents

and pints

and Fred Perry polos

and other invisible clothes

of the labour aristocracy.

We reject their complicity.

It’s not for self appointed

tribune of the plebs,

to sacrifice its words for the wider movement

or people who think

there’s only one way to be bled

or only one way to be led,

demanding no more be said.

This is a poem for the nameless,

these shrieking calibans, whose feet

tell stories through their soles, marking dirt roads

This is for the homeless,

perpetual picaros, the shrapnel collectors,

and those unlucky

to die in the Birmingham snow. Therefore

in the cities we seek,

finding the margins on the streets,

an otherwise

in the underneath.

Through the basement door

we find

rhythms with autonomy

nothing uniform,

for they don’t follow the factory march anymore.

Down here

the lumpenproles

prepare

to take the floor.

We, slipping doven words between prison bars

this ammunition, giving bars, spat like tactile bullets

on the frontline of the class war.

This is not a manifesto made

for readers to click their fingers at,

to let your satisfaction

solidify like syrup around it;

provocations should never sit

easy.

From that, we declare

we do not sit with clean people,

we sit with the cleaners.

We take the side of the many medeas

bathed in the ashes of cradle fires.

We links arms

with murders and thieves

and say,

there are landscapes here,

within.

Stone butch blues sing of many wounds

and we’ll tend them too,

these chimeras, these

genderqueer guerrilas,

our movement holds many things,

and at the lowest level,

we hold many things.

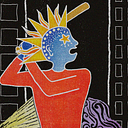

Here’s to hooligans,

singing in chorus

with Crazy Horse to the last violent breath,

who dance in the quiet streets,

to summon the memory of a

riot.

Their make up comes from blazes,

so many, which they are tired of, but still

they dance

Each step, a syllable

of the message they bring.

The hooligans reject their turn

and shout:

we are not the terror,

we are the ones

who kill it.

II.

The person who writes this,

the poet,

is not an authority to be trusted.

He is not a genius, for

his words, reacting with the ariel air,

are soon found rusted.

His voice is only important

in the provoking of what is truthful,

when the ink has dried, when the poem is published,

he ceases to be useful.

If he had to be described;

if we should ever need to speak of a writer

the term best suited for him

is a bull fighter.

He is one

of two violent creatures,

destined to dance, that is,

in matadorial flourishes

if we chose to speak in romance.

He doesn’t dart around his opponent,

but instead,

let’s the bull get closer than he can really afford,

this is because, if you didn’t know,

the deepest wounds are struck,

when you let yourself be gored.

This duo, once sensitive,

are now prime bred to hurt.

And one will have the reward

of dying in the dirt.

His opponent is every other thing like him — alive,

he finds it in the reflection of his enemy’s eyes.

His struggle sits as a problem;

it’s a space

of blood drying in the sun.

Ask yourself,

in the end,

who’s actually won?

The poet,

at best, in the last,

is merely a bullfight,

and

that kind of revolutionary is past.